“A children’s story that can only be enjoyed by children is not a good children’s story in the slightest.” – C.S. Lewis

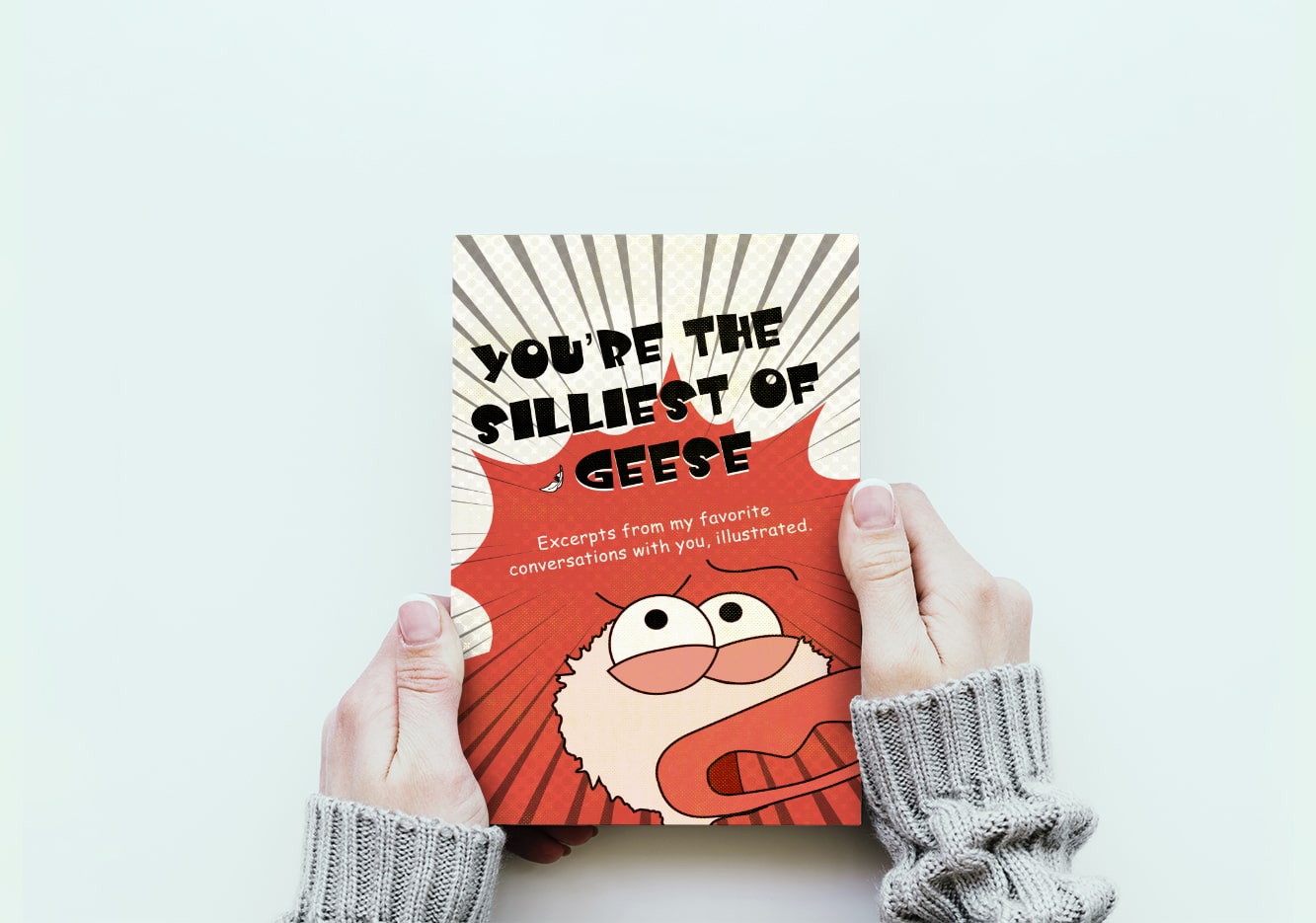

Children’s Book That Lives Beyond Childhood

Your path to becoming a children’s book author

In the age of AI story generators, screen-saturated kids, and TikTok bedtime distractions, writing a children’s book isn’t just about cute rhymes and candy-colored characters. It’s about crafting a cultural artifact that can outlast trends, cross age lines, and live on coffee tables long after the intended reader has outgrown it.

It’s not enough for your story to be “for kids.” It has to be worth remembering. Here’s how to get there.

Planting the Seed

The Origin Story of Your Origin Story

Every iconic children’s book starts with a spark a runaway thought that refuses to sit still. J.K. Rowling met hers on a delayed train. Maurice Sendak’s ‘Where the Wild Things Are’ grew from a simple concept into a global childhood rite of passage.

Your spark might be a conversation overheard in a café, the way your niece mispronounces “hippopotamus,” or a mental image you can’t stop replaying. The key is to protect that seed before overthinking strangles it.

Pro tip: Keep a “story bank” a digital or analog notebook for snippets, lines, characters, and moments. Most won’t become books, but one will change your career.

The Golden Thread

Message Before Magic

Pretty illustrations and clever rhymes mean nothing without a through-line. Your “golden thread” is the emotional current that keeps a story from being disposable. Aesop’s fables stitched morals into memory. Shel Silverstein made children laugh and adults cry with the same line.

Ask yourself:

- Is this a lesson, an escape, or both?

- Would I still care about this message if no one bought the book?

Stories that resonate beyond childhood have one thing in common: they speak to humans, not just “kids.”

Knowing Your Readers

Little and Big

A toddler’s literary universe is board books, textures, and repetition. A 10-year-old’s is sprawling worlds and layered humor. The tone of ‘The Very Hungry Caterpillar’ would flop in middle grade; the pacing of ‘Percy Jackson’ would baffle a preschooler.

Pro tip: Don’t “write down” to children. Write clearly. Lewis Carroll and Beatrix Potter understood this they created worlds with depth, then trusted children to keep up.

The Sculptor’s Mindset

Writing and Revising

Your first draft is wet clay. The shaping happens in the rewrite. E.B. White rewrote ‘Charlotte’s Web’ until every word pulled its weight.

Edit like this:

- Through a child’s eyes: Will they feel this?

- Through a parent’s ears: Will they enjoy reading it aloud for the 100th time?

- Through your own lens: Does it still excite you?

Feedback from actual children is gold but watch their reactions more than their words. Kids are honest in the way they squirm.

The Visual Heartbeat

Illustration as World-Building

In children’s books, illustrations aren’t decoration; they’re narrative oxygen. Quentin Blake didn’t just draw for Roald Dahl, he became part of the storytelling DNA.

Finding an illustrator is like choosing a dance partner. The rhythm has to match, the style has to fit the soul of the story. If you’re the illustrator, challenge yourself to make each page a place a child would want to live in.

Pro tip: Test spreads in grayscale before adding color. If the story still works, your visual storytelling is strong.

Publishing Pathways

Choose Your Adventure

| Category | Traditional Publishing | Self-Publishing | Winner |

|---|---|---|---|

| Editorial & Design | • Professional editorial, cover, and layout team• Limited creative control | • Full creative control• Must hire and manage your own team | Tie |

| Marketing | • Built-in marketing and PR support• Publisher controls approach | • You decide all marketing strategies• Marketing is fully your responsibility | Tie |

| Credibility | • Industry prestige• Highly competitive to get accepted | • Build credibility through audience and reviews• Slower credibility growth | Traditional |

| Payments & Royalties | • Possible advance payments• Lower royalty rates | • Higher royalty percentage• No advance payments | Self |

| Distribution | • Access to bookstores and libraries• Limited say in formats and territories | • Global online reach• Harder to get into physical stores | Traditional |

| Speed | • Professional, structured process• Slow timelines (often 1+ year) | • Fast to market (weeks or months)• Risk of rushing production | Self |

| Rights | • Publisher handles legal aspects• Publisher may hold some rights | • Retain full rights• Must handle all legal matters | Self |

| Costs | • Publisher covers production costs• Lose budget control | • Control your own budget• Upfront production costs | Self |

Rowling’s Hogwarts began in traditional publishing. Beatrix Potter’s ‘Peter Rabbit’ started self-published. The right choice depends on your appetite for control versus infrastructure.

Marketing

The Story After the Story

Writing the book is the prologue to its real life in the world. Chris Van Allsburg’s ‘The Polar Express’ didn’t become a Christmas staple by chance it rode a wave of grassroots marketing, school readings, and seasonal nostalgia.

Today, your bridge to readers spans Instagram Reels, author TikToks, and live readings at schools. A book trailer isn’t optional; it’s a scroll-stopper.

Pro tip: Market to parents, teachers, and librarians they’re the actual gatekeepers of children’s literature.

Brand You

Becoming a Name Readers Trust

Neil Gaiman isn’t just an author; he’s a persona. In the children’s book world, your name is a brand.

Start with a website that feels like your book looks. Keep social media authentic behind-the-scenes sketches, cover reveals, Q&As with kids. Build relationships with other authors. In this space, cross-promotion beats competition every time.

Reading List

For the Story Architect

- Aesop – Fables: “Simple tales that have echoed moral truths for centuries.”

- Beatrix Potter – The Tale of Peter Rabbit: “Creative control turned into a cultural legacy.”

- J.K. Rowling – Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone: “Transforms imagination into a shared universe.”

- Maurice Sendak – Where the Wild Things Are: “Shows restraint can be the loudest voice.”

- Quentin Blake & Roald Dahl – Matilda: “Turns mischief into a noble art form.”

- Shel Silverstein – The Giving Tree: “Minimalism that leaves a lasting ache.”

- Chris Van Allsburg – The Polar Express: “Captures the magic of belief in every page.”

- E.B. White – Charlotte’s Web: “Teaches empathy without ever preaching.”

Final Thought

Why This Matters More Than Ever

We live in an attention economy where every screen fights for a child’s gaze. A great children’s book isn’t competing on noise; it’s competing on memory.

If you do it right, your book won’t just entertain it will live inside someone for decades, resurfacing when they read it to their own kids. That’s the quiet power of the form: it shapes future adults, one bedtime story at a time.

So write for the child. But aim for the human.

References

- Lewis, C.S. (1982): On Stories: And Other Essays on Literature

- Rowling, J.K. (1997):Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone

- Sendak, Maurice (1963):Where the Wild Things Are

- Aesop (c. 600 BCE):Fables

- Silverstein, Shel (1964):The Giving Tree

- Carle, Eric (1969): The Very Hungry Caterpillar

- White, E.B. (1952): Charlotte’s Web

- Blake, Quentin and Dahl, Roald (1988): Matilda

- Van Allsburg, Chris (1985): The Polar Express

- Potter, Beatrix (1902): The Tale of Peter Rabbit